2000s: Texas Independence

The first decade of the new millennium for the Texas moving image industries was a continuation of the trends that developed in the decade preceding it. Major productions continued to stream into the state, and Texas continued to be called upon time and again to represent Everytown, USA. But as the 2000s kicked off, several trends not only continued but evolved, and still define the state to this day. One of particular note is the ascendancy of several homegrown filmmakers from indie darlings to mature—but no less independent—storytellers, craftspeople, leaders and mentors who helped lay the track and pave the way for the next generation to follow. This was a decade of independents and independence, of Texas continuing to step boldly into the future to prove that anything that could be done beyond its borders, could just as well be done within. But before we dive into that, there are a few projects from the early years of the 2000s that simply cannot be overlooked.

A pair of films released on December 22, 2000 would go on to break the top 100 highest grossing films of the year, despite their only being in theaters for a scant nine days. Beyond the box office success, their similarities are few and far between. The Sandra Bullock-starring Miss Congeniality tells the tale of an FBI agent who goes undercover at the Miss United States pageant in order to catch a terrorist threatening the event. Robert Zemeckis’ Academy Award-nominated Cast Away tells the story of a FedEx executive stranded on an uninhabited island and his struggle to survive over four long years. Narrative differences aside, the production of the two films were none too similar either. The pageant at the center of Miss Congeniality takes place in the heart of San Antonio and, as such, the production also filmed in nearby Austin and Round Rock. Conversely, Cast Away sets only a single scene in Texas and considering it’s the final scene of the film, we won’t spoil it here for those of you who still haven’t gotten around to watching. Suffice it to say, the film makes fitting use of the natural beauty and abundance of wide-open, rural splendor in Texas, setting the scene in the Panhandle cities of Canadian and Mobeetie.

BTS Still from Spy Kids (2001) / © Dimension Films

2001 saw the first in a parade of high-profile releases from born-and-bred Texas filmmakers that would continue throughout the decade. Spy Kids would mark the first—though far from the last—Robert Rodriguez movie of the 2000s to grace the big screen; he would release seven films, all of them shot primarily in Texas and all of them, to varying extents, working in some way to push the boundaries of digital filmmaking and elevate the craft further into the mainstream. Fellow Austinite Richard Linklater also found himself drawn in by the allure of freedom that advancements in digital technology provided as he produced two experimental rotoscoped films around the same time: Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006). While Rodriguez experimented with 3D, CGI and digital video to increasingly greater extents over the course of the Spy Kids movies, Linklater could be found filming around Austin and San Antonio, oftentimes featuring local talent and personalities, before passing the footage over to a team of Texas animators who then drew atop each individual frame by hand, giving the films a transitory, dreamlike air.

2005’s Sin City can be considered the apotheosis of Robert Rodriguez’s newfound digital freedoms, pushing the nascent technology all the way to the forefront of the picture. Filmed shot-for-shot to match frames from the graphic novel from which it drew its inspiration, what viewers saw was almost entirely a fabrication coming out of Troublemaker Studios, real actors performing in front of a computer-enhanced world that vaguely mirrored our own, as reimagined through a variety of neo-noir elements. Rodriguez himself heralded such developments in the digital filmmaking process on the set of Spy Kids 2, remarking, "This is the future! You don't wait six hours for a scene to be [lit]. You want a light over here, you grab a light and put it over here. You want a nuclear submarine, you make one out of thin air and put your characters into it." These technological advancements required something that Texas had been investing in along several different avenues throughout the decades leading up to the 2000s—infrastructure.

The infrastructure supporting the moving image industries in the state during the first decade of the 2000s was multifaceted and extended far beyond the practical physical structures available to productions, though there certainly were a great deal of those available. Numerous Texas-based production spaces were frequently used by film and television productions throughout the decade, from the Richard Linklater-founded Austin Studios to Rodriguez’s own Troublemaker Studios, as well as the Studios at Las Colinas up in Irving, which became Mercury Studios in 2002, and so on. By investing in physical infrastructure, Texas was able to marry its natural resources with its capital resources and provide a full range of options to film and television productions so that almost anything creators could imagine could be taken care of in-state. The list of productions that utilized these and other spaces to varying extents during the 2000s is long and varied; it encompasses everything from Kimberly Peirce’s Iraq War drama Stop Loss (2008) to John Lee Hancock’s feel-good baseball flick The Rookie (2002) and the Tommy Lee Jones-starring Man of the House (2005) to The Life of David Gale (2003), the crew of which constructed an imposing exterior prison set for the film on the Austin Studios backlot, and many more.

Still from American Outlaws (2001) / © Morgan Creek Entertainment

Visit the Texas State Railroad

This is not to say that film production was relegated entirely to studio spaces. An abundant natural resource in Texas has always been the breadth and diversity of our geography, the unique and multifarious regions that make up the land within our borders, and productions continued to recognize and utilize that resource frequently. It was around this time in 2007 that the Texas Film Commission launched the Film Friendly Texas community certification program to train and equip Texas communities large and small on best practices in order to effectively accommodate and welcome media production industries. While the program has more than 150 certified Texas communities today, nearly 15 years ago production was on the move and community representatives were anxious and ready to learn more about hosting these industries. In fact, at the same time the aforementioned studio spaces were filling up, several oft-underutilized regions of the state saw a marked increase in film and television production. Denzel Washington chose to film his second directorial effort The Great Debaters (2007) in the East Texas towns of Palestine and Marshall, home of the Wiley College debate team at the center of the film, and 2001’s American Outlaws made notable use of the region when it also featured Palestine as well as the storied Texas State Railroad on the outskirts of Rusk, Texas.

The West Texas and Trans-Pecos regions also proved enduringly popular throughout the decade with a host of small towns taking their place in the spotlight. Towns like Shafter, Lajitas, Redford, Canyon, Monahans and Van Horn made their way onto the big screen in The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2005); Disney’s sports drama Glory Road (2006) chose to film their story of UTEP’s (then Texas Western College) run at the 1966 NCAA Basketball Championship in El Paso. Embracing the film business entirely, El Paso would also host Tony Scott’s Denzel Washington-starring Man on Fire (2004), the disaster epic The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and Ethan Hawke’s The Hottest State (2006). Two films that would eventually go on to compete against one another for Best Picture at the Academy Awards, 2007’s There Will be Blood and No Country for Old Men, both set up production in the Big Bend region’s desert oasis of Marfa at the same exact time for a few exciting months of production in 2006.

The Central Texas region of the state, ever important in the history of the Texas moving image industries, saw consistent interest throughout the decade as well, most notably in the realm of television production. While numerous pilots filmed in and around the Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth and San Antonio areas throughout the 2000s, a few TV series stand out from the rest: Prison Break (2005-2009) told the story of a man sentenced to death for a crime he did not commit and the elaborate plan his brother devises to spring him from prison and clear his name. The crew behind Prison Break made their way down to Texas to film the second and third seasons of the show all over the Dallas-Fort Worth area. In addition to creating a Panamanian prison in the Stockyards District of Fort Worth that would serve as a reoccurring set for a series arc, over the course of two seasons several smaller towns in the area would also be called upon to stand in for small towns from all over the United States. In this way, North Texas towns like Decatur, Little Elm, Pottsboro, Greensville and McKinney all found their way onto an estimated 9.3 million screens across the nation.

Still from Friday Night Lights (2006-11) / © NBC

The other series from this era that absolutely cannot be overlooked is the beloved Texas high school football drama Friday Night Lights (2006-2011). Inspired by the true story of the 1988 Permian Panthers run for the state championship, Friday Night Lights focused on the fictional small Texas town of Dillon and the individuals caught up in the world surrounding the local high school football team, the Dillon Panthers. Though the series was never able to attract a large audience, it proved a critical darling and consistently garnered strong, effusive praise for its humanistic representations of small-town Texas life and all the joys and complications that come with it. The series filmed all over the greater Austin area in the course of five seasons, primarily in Austin, Del Valle and Pflugerville, but branched out as well into the surrounding areas of Westlake, Georgetown, San Marcos and Taylor.

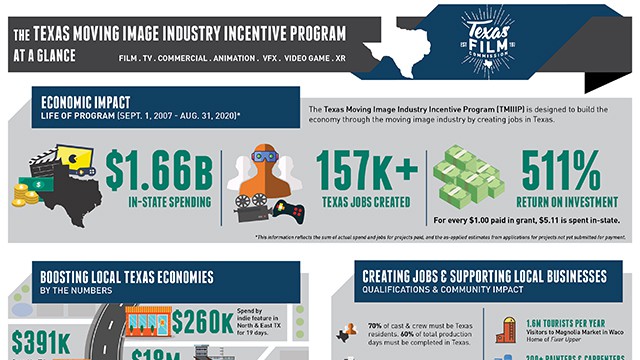

No matter which corner of Texas they happened to film in, each of these productions was in some way, shape or form bolstered by the guidance, support or services of the Texas Film Commission, itself an instrumental part of the varied tapestry of infrastructure supporting media production in the state. Many of these productions even benefitted from the newly created Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program (often referred to simply as TMIIIP), a grant program established in 2005 and funded in 2007 with the aim of building up the Texas economy through the state’s moving image industries. Over time, the grants provided by this program have resulted in over 157,000 jobs created and a return on investment that creates $5.11 in local spending for every dollar in grants paid.

Still from Star Wars: The Old Republic / © BioWare

The Texas Film Commission wasn’t the only organization interested in expanding the workforce and cultivating a local talent pool around this time. Much in the way Texas independent filmmakers were evolving and maturing, so too was our local video game development community, as evidenced by the establishment of SMU’s prestigious Guildhall in Dallas in 2003 at the behest of the game development industry to train its future leaders. Guildhall is a graduate program focused specifically on the field of Game Development, with alumni at more than 270 video game studios around the world, including several right here in Texas. Serving the digital media industries, it joined the likes of Texas A&M’s Visualization Laboratory, a program started in 1988 in response to “indications that digital visualization was going to play a highly important role in digital communication.” Built in collaboration with some of the state’s most influential and acclaimed video game studios, including id Software, NC Soft and several others, Guildhall currently ranks third on the Princeton Review’s list of Game Design programs, and rose to prominence alongside newer Texas studios like Gearbox, Certain Affinity and Arkane Studios. These companies would in turn draw upon the deep well of talent therein to fill out their own rosters as they worked on some of the biggest games of the 2000s. Just a few years after first opening their doors, Frisco-based Gearbox would help to develop the PC port of Halo: Combat Evolved (2003), a game generally considered among the most influential of its time and credited with helping to modernize the gaming genre that Texas-created Doom and Wolfenstein helped to popularize the decade before. At the same time, the artists at BioWare Austin could be found hard at work on Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (2003), a game released to universal acclaim that would go on to be declared the Game Developers Choice Awards’ 2004 Game of the Year. And just a few years later, Austin-based Certain Affinity would close out the decade working on one of the most successful franchises in video game history with the critical and commercial success, Call of Duty: World at War (2008).

Throughout all of this, a movement had been developing across the state, one that strongly resembled that of the independent filmmaking boom of the 1990s that had helped to establish the idea of Texas as fertile ground for independent, creative, vital storytelling. This new wave of filmmakers built upon the ground laid for them by their forebears, the indie trailblazers of the 90s and the pioneers of the 70s alike, as they made intimate, personal projects that captured the sentiment and emotion of the cultural moment as they experienced it, with films like Kat Candler’s Jumping off Bridges (2006), David Lowery’s St. Nick (2009), Andrew Bujalski’s Beeswax (2009), Amy Talkington’s Night of the White Pants (2006), the Zellner Brothers’ Goliath (2008), Yen Tan’s Ciao (2008) and the Duplass Brothers’ Vince Del Rio (2003). By the time these filmmakers began making movies in earnest, the technology required to do so had become much more affordable, on a scale never before seen. In a sense, it was easier to make a movie than it ever had been up to that point in time. Easier, however, does not directly translate to easy, and it was in large part because of the examples of trailblazers like Linklater, Rodriguez, Mike Judge and even the elder Terrence Malick that this next wave of independent filmmakers had the conviction to produce films with a proper, DIY independent spirit. The collaborative nature that had been well established in an accessible, creative community was primed and ready for them. With commitment, determination and extreme resourcefulness, this new wave of Texas filmmakers made its way into the public eye and helped to keep Texas on the map as a place with a deep well of emerging voices.

Houston Cinema Arts Festival (2009) / Photo: Houston Cinema Arts Society

One of the key components for a state hospitable to independent filmmaking has been the exhibition opportunities provided by the cottage industry of film festivals and conferences that had sprouted up all across the state by this time. While the well-established South by Southwest (SXSW) was maturing into a respected industry marketplace and the Austin Film Festival seized the moment to help celebrate screenwriters emerging from the new golden age of television, regional festivals also helped to amplify and embrace Texas filmmakers, creating an invaluable exhibition space for local voices. In 2007, Dallas and Fort Worth welcomed the Dallas International Film Festival (formerly AFI Dallas) and the Lone Star Film Festival respectively. Further south, Fantastic Fest was taking shape in Austin and providing a home for genre-pushing, outré filmmakers to present their work alongside others of a similar far-out disposition. The emergence of the Houston Cinema Arts Film Festival proved especially important in this period in establishing definitively the idea of Houston as “a thriving arts town that celebrates innovative films, media installations and performances.” Even cities like Fredericksburg and Marfa created destination festivals that continue to take audiences outside the big cities to celebrate the movie-going experience with local flavor. All of these festivals, as well as scores more not listed here, helped to piece together a living ecosystem of support across Texas that has only grown stronger in the years since, with more than 100 film festivals of all shapes and sizes statewide.

By the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the Lone Star State had a steady rhythm of film, television and digital media production, but competition was beginning to grow fierce as projects became conditioned to chase incentives and competing jurisdictions emerged. That said, the story of both the Texas Film Commission and the Texas moving image industries across this decade is still one of growth, maturation and innovation in every regard. Be it our physical, natural, organizational or human infrastructure, each and every aspect continued—and continues—to build off the work of the years before. The decade to follow, the final in our look back at our own history, would showcase evolution and resilience, proving to be the summation of all that Texas had experienced to date. The demand for content and the growing tech sector would bring opportunities for convergence, and it should come as no surprise that Texas would be ready for another seismic shift in the media production landscape as new technologies and the spirit of entrepreneurship would help to cultivate a stronger and more dynamic business climate and creative community.

Next: Fostering the Creative Community in the 2010s

Written and edited by Steven McCaig, Ali Nichols, Leigh Davis and Lindsey Ashley.

Film Friendly Texas

The Film Friendly Texas program was created in 2007. Now at 150+ communities, the program continues to train Texas communities large and small on best practices in order to effectively accommodate and welcome media production.

Texas Moving Image Industry Incentive Program

The Texas Film Commission has attracted $1.66 billion in local spending and created more than 157,000 production jobs across the state from 2007 to 2020.

Festivals & Conferences

Festivals have helped to piece together a living ecosystem of support across Texas that has only grown stronger in the years since with more than 100 film festivals of all shapes and sizes happening statewide.