1990s: Spotlight on Texas

If the 1970s were the era where the seed of what the Texas moving image industries would eventually grow into was first planted, and the 1980s the adolescent years of growth and expansion, then the 1990s were the decade Texas finally blossomed into what became the Third Coast of American media production. As budgets ballooned and studios vied to go bigger than their competitors, Texas continued to make good on its reputation as a premier destination for film and television production. There is perhaps no better way to describe this particular period of Texas media production history than with Davy Crockett’s famous quote: “You may all go to hell and I will go to Texas.” But while the decade would be marked by a staggering influx of Hollywood productions, it would begin with a project from a filmmaker who would one day become an elder statesman of the Texas film scene. The filmmaker? Richard Linklater. The film? 1990’s Slacker.

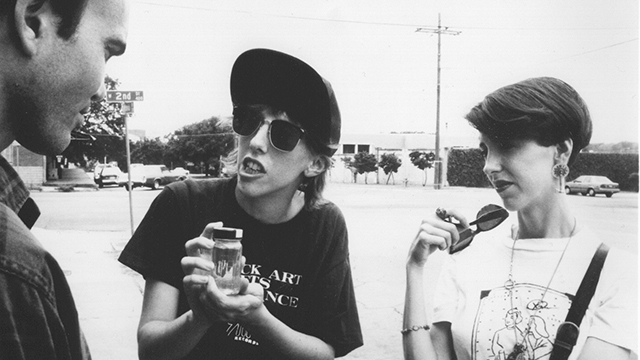

Still from Slacker (1990) / © Detour Filmproduction

It’s interesting that the film that would kick off the state’s most high-profile decade since the Texas Film Commission’s inception—as well as the career of one of its most celebrated sons—is, in effect, a film about nothing in particular. And yet Slacker, an ensemble piece following various artists, writers, musicians and (of course) slackers as they meander through a seemingly ordinary day, somehow manages to simultaneously be about everything. In vignette after vignette, we are introduced to a variety of personalities, each tied in some way to the one preceding and yet still wholly unique, each representing a different shade of the spectrum that made up Austin at that moment in time.

Austin was still very much a relatively small town by any metric. Despite laying claim to the state capitol building and the University of Texas, Austin’s 1990 population was only 465,622 Texans, compared to, for instance, Houston’s 1,631,766. This establishes a theme that would carry throughout the decade—that in spite of the fact that three major metropolitan areas lie within the state’s borders, Texas was a state made up predominately of small towns. Perhaps due to the state’s abundance of diverse regions that enabled Texas to stand in for a wide variety of American locales, time and again throughout the 90s, productions, be they independent or big-budget studio fare, would call upon Texas to represent small town, traditional America on the big screen.

Featuring Linklater himself, alongside several Austinites who would go on to influence Texas in their own right such as SXSW founder Louis Black, cinematographer Lee Daniel and more, Slacker was the first shot across the bow to the world beyond the state lines, heralding the fact that (much as it had in the 1970s) something altogether new was stirring down in Texas. Despite never receiving a wide release, it would go on to gross more than 53x its budget, bringing in $1,228,108 and making the case for Linklater to be given a much bigger budget for his follow-up film, Dazed and Confused (1993). But before that film would ever grace the silver screen, Hollywood would make its way to Texas in the form of two radically different films: one a political thriller with roots running deep through the fabric of Texas history, the other an intimate drama revolving around a young man caring for his overweight mother and intellectually disabled brother.

Oliver Stone’s 1991 epic JFK, starring Kevin Costner, fresh off two Academy Awards for Dances With Wolves, and featuring a smattering of Hollywood and Texas acting icons, centers around one of the darkest moments in modern Texas history, the assassination of the 35th President of the United States in Dallas and the investigation, conspiracy and myth that followed it. A towering, labyrinthine film spanning over three hours, it could not be further removed from the next big Hollywood production to come through the state, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993)—a sentimental story best remembered for its portrayal of the peculiar but loving Grape family, led by put-upon elder brother, Gilbert played by Johnny Depp. Austin, Pflugerville, Manor and Lockhart were used to bring to life the small town of Endora, Iowa, as once again Texas was called upon to portray Everytown, U.S.A.

The real unifying element linking these productions is not in content, form, or intent, but in the external forces working diligently on their behalf during their respective stints in Texas. These films were but the first wave of studio productions to roll in from the west coast and through the state in the 1990s, a great many of which were supported by resources only available in a region where a film commission had been in existence for over two decades. The Texas Film Commission assisted these, among dozens of other productions, in their effort to find suitable filming locations, liaise with local city governments and (in the case of JFK) shut down busy thoroughfares, reroute city buses and create, for a brief window in time, a fictional world in the midst of a very real, very busy one.

Hollywood productions turning to and partnering with the state and regional film commissions for services was a trend that would continue throughout the coming years, be it in service of A Perfect World (1993—a return trip to Texas for Kevin Costner), Blank Check (1994), Reality Bites (1994) or any of the other myriad films clamoring to shoot in Texas. As film productions stumbled over one another to set up shop on the Third Coast, a different sort of production was simultaneously extending its roots deeper into the media landscape, one that would end up not on the big screen, but the computer screen.

Still from Ultima (Photo Credit: PC Gamer)

Texas is in fact, the third-largest state in the U.S. for video game development. In order to properly explain this facet of digital media history in Texas, we must first roll the clock back a bit to 1981 and the release of Richard Garriott’s Ultima. Developed during his time as an undergrad at the University of Texas at Austin, Ultima was one of the first commercial computer Role Playing Games (RPGs) released for the Apple II, ultimately selling 50,000 copies. With this success, Garriott was able to publish Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress the following year, and with the release of Ultima III: Exodus in 1983 was able to launch Origin Systems.

An argument can be made that the Texas video game landscape was born with Richard Garriott, Origin Systems and the success of the Ultima series. In the wake of this success, two of the most influential developers in video game history also planted their flag here. And as we roll the clock forwards again to 1992: Richardson-based id Software and Garland-based Apogee Software Productions (now 3D Realms) release Wolfenstein 3D, a game generally considered to be one of the most influential ever made.

For most businesses, such a success might be considered the apotheosis of a career, but neither game studio was prepared to rest upon its laurels. While Wolfenstein 3D can be considered the first game-changing success for both id Software and Apogee, each studio would release at least one more noteworthy game of influence before the decade finally came to a close. With the release of Doom in 1993, id Software would be the first to cross that threshold and Doom would go on to be one of the first games submitted for inclusion in the Library of Congress’ ‘Game Canon’. Apogee may not have received the same level of critical recognition, but with the release of Duke Nukem 3D in 1996, they would cement their position in video game history.

As these developers worked furiously crafting video game history in the greater Dallas region, the wheels of the film and television production industry continued to turn across the state. In the spring of 1993, future Academy Award winner Paul Haggis and Leslie Greif would introduce the world to a character that would become a long-lasting, bonafide Texas icon. Walker, Texas Ranger, starring Chuck Norris in the titular role as Cordell Walker, would run for an action-packed eight seasons in over 100 countries before finally calling it quits in 2001. Like the Dallas TV series that came before it, the show’s legacy would prove too strong to keep off the air; in January 2021, 20 years after its cancellation, a Walker reboot would premiere, produced by CBS Television Studios with Norris’ blessing.

Hollywood would again come calling in 1995 with Ron Howard’s Apollo 13, which looked to imbue its story with authenticity by filming at the Houston-based sites of the historic events featured in the film. Starring Tom Hanks, Kevin Bacon and Fort Worth’s very own Bill Paxton, and featuring an uncredited rewrite by iconoclastic independent filmmaker John Sayles (more on him later), the film depicts the events surrounding the ill-fated Apollo 13 lunar mission and was filmed partially on-site at Ellington Field and the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Still from Lone Star (1996) / © Columbia Pictures

Explore the Border Towns of Lone Star

1996 would prove to be a big year for Texas, as well as moviegoers who would see the Lone Star State on the silver screen, as Texas productions hit theaters one after another. Tin Cup, starring Rene Russo and Kevin Costner, would finish the year as the 26th highest grosser of 1996; Nora Ephron’s Michael, released at the tail end of the same year, would also perform well, ranking it 26th at the box office in 1997. Others were smaller, though their legacies loom larger. Wes Anderson’s debut feature Bottle Rocket, for instance, introduced the world to just a taste of his unique sensibilities as a filmmaker, not to mention the Wilson brothers, Owen and Luke. Waiting for Guffman, Christopher Guest’s ensemble comedy, showcased the small-town thespians of Blaine, Missouri, by way of Lockhart, Texas. And the aforementioned John Sayles’ Lone Star, a western murder mystery set and shot all along the Rio Grande, made extensive use of rural towns like Del Rio, Uhland, Coupland, Lajitas and more. Described by the Dallas Observer as creating a world similar to William Faulkner’s famed fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Sayles “examines the complex social, political and familial histories” of South Texas, something all too rarely seen on-screen to this day. It holds the distinction of being the first film to be shot in the border town of Eagle Pass and was estimated by the Eagle Pass Chamber of Commerce’s Executive Director in 1996 to have had a $2 million impact on the local economy (translating to roughly $3.4 million in today’s dollars).

On March 16, 1996, an estimated 6,000 people lined up through San Antonio's El Mercado/Market Square to audition for the title role in the film Selena. (Video: Texas Archive of the Moving Image / Fred Miller)

1997 would shine as a year when one of the state’s most beloved homegrown musical icons would grace the big screen before a much-deserved worldwide audience. Based on the life and career of the ‘Queen of Tejano’ herself, Selena told the story of the singer’s rise to stardom and tragic death. Released not two years after the heartbreaking passing of Selena Quintanilla, over 6,000 individuals in San Antonio alone auditioned for the title role before rising star Jennifer Lopez helped to embody the singer’s profound legacy in music, fashion and popular culture. Embracing the authenticity of Selena’s upbringing, the film uses a variety of Texas locations to great effect, including Lake Jackson, Aransas Pass, Corpus Christi and San Antonio. Perhaps most memorable are the scenes featuring the star’s rise to prominence among the world-famous River Walk in San Antonio. A box office success, Selena would remain in the Top 10 for four weeks straight and end the year as the 59th highest grossing film of 1997. Dancing her way into the hearts and minds for generations to come, this larger than life story continues to be celebrated and re-imagined, properly acknowledging the South Texas culture and heritage that helped to shape Selena’s sound and style.

The waning years of the decade would see a cavalcade of high-profile films roll through the state. In 1998 alone, an impressive number of Texas’ brightest stars would release movies produced entirely within their home state: Richard Linklater’s indie/Hollywood crossover The Newton Boys, starring Texas natives Matthew McConaughey and Ethan Hawke; Wes Anderson’s Rushmore; Robert Rodriguez’s The Faculty (his fourth film chronologically, but first to roll cameras primarily in Texas); and Forest Whitaker’s Hope Floats, starring future Texas import Sandra Bullock. To try to compare these four films would be an exercise in futility, as their aims, as well as their intended audiences, vary from picture to picture. Regardless, a few facts are true about each of them: They were all made by native Texans who would eventually mature into prolific, culture-driving artists whose work fellow Texans could watch with great pride. But in this particular moment, they would all inevitably end up dwarfed in the public eye by the release of Michael Bay’s mega-hit, Armageddon.

Showcasing a variety of North Texas locations, including Sanger, Aubrey, Denton, Pilot Point, and then moving towards the Gulf Coast for an oil rig off of Galveston Island while also featuring the Johnson Space Center, Armageddon tells the story of humanity’s last-ditch effort to stop a gigantic asteroid from colliding with earth by sending blue-collar, deep-core drillers to split it down the middle. Despite Roger Ebert’s protestations that the film was “an assault on the eyes, the ears, the brain, common sense and the human desire to be entertained”, audiences disagreed in droves, sending the film all the way to 2nd place at the year-end box office, behind only Titanic. When it was all said and done, five films with Texas in their DNA would also land on the same year-end list, including the aforementioned Hope Floats (31st) and The Faculty (94th), Jonathan Demme’s Beloved (84th) and Robert Duvall’s The Apostle (89th).

They say everything old is new again, and in 1999 we can see the wisdom of just such a statement. The final year of the decade saw filmmakers looking forward to the new millennium and wrestling with ideas that, though they would come to occupy increasingly larger swaths of the cultural landscape, can trace their cinematic roots back through the decades before them. Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry, for instance, tells the true-life tragedy of Brandon Teena through an unflinching, neorealist’s eye that Peirce aims at some of the central themes that continually surface throughout the history of Texas filmmaking. No one topic is more effectively dissected than the very idea of identity, individual as well as societal, and Peirce’s effort at exploring identity was widely recognized for its cultural significance through a variety of award nominations, wins and critical acclaim. An additional element of the film linked it intrinsically to so many of the Texas films before it as well—once again, yet another Texas community was called upon to represent Everytown, America. This time it was the North Texas city of Greenville standing in for Teena’s hometown in rural Nebraska.

Still from Office Space (1999) / © Twentieth Century Fox

Just a few months earlier though it had been the Austin and Dallas areas representing suburban America in general and adopting a very different tone. Though the film ostensibly takes place in Texas, Mike Judge’s Office Space could be transported easily into any of the greater metro area office parks across the United States. A satirical look at the seemingly meaningless and mundane lives of white collar-workers in the tech-sector dotcom bubble, the film perfectly captures the existential frustration that many Americans, Texan or otherwise, felt then and continue to feel now at the idea of working jobs that offer them with very little in the way of personal satisfaction and fulfillment. Filled with beige cubicles, harsh fluorescent lights and all the hallmarks of stereotypical bureaucratic corporate culture, the film finds humor in a general malaise that was beginning to bubble to the surface of the American middle class. Perhaps because of all of these things, the film was destined to become an object of cult-like affection. Though it only grossed a bit more than it cost to produce, the legacy of Office Space grows with each passing year—just recently, it was compared by New York Times Magazine to the classic Herman Melville short story Bartleby, the Scrivener, and likened in its dissection of tedious mundanity to the works of Franz Kafka.

It is important to note as well that throughout the decade, the spotlight did not fall exclusively on the narrative storytelling and video game sectors of the production industry, but on Texas’ commercial production sector as well. In many regards, commercials in the 1990s served a very similar purpose in Texas to made-for-TV movies in the 1980s—they helped to train and strengthen our local crew, providing financial injections into regional communities and sustaining them during the periods between longer television and feature film work. Whether or not a production could afford to travel oftentimes depended upon the existence of a dedicated and highly skilled local crew base, which, thanks to the two preceding decades, Texas was flush with. As we continue to march through the decades, there can be no question that Texas’ local crew was, and continues to be, one of our most valuable resources.

Suffice to say, the 1990s was a robust decade for the Texas Film Commission and the creative community in general. The years to follow would also prove to be busy, though the story of the 2000s takes an unsuspecting turn. The decade to follow would see the landscape of the Texas media production industry continue to shift and evolve; the rise of a multi-faceted media scene, including infrastructure developments made for indie darlings hungry to forge their own paths through the Lone Star State; the evolution of new-tech trailblazers and mentors; and the establishment of financial incentive programs that would change the face of the media production business model forever.

Continue: Texas Independence in the 2000s

Written and edited by Steven McCaig, Katie Kelly and Matt Miller. Thank you to our guest editor, Heather Page, who served as director of the Texas Film Commission from 2012–2017.