1970s: Decade of the Pioneer

In 1971, the year the Texas Film Commission first opened our office doors, Austin was not what you would call a big city. Certainly one could not have predicted that the state capital, nestled in the cradle of the Texas Hill Country, would one day evolve into the cultural behemoth it is today. Likewise, one would be hard-pressed in those early years to predict the impact that the Texas media production industries would have on a state nearly equidistant from both Los Angeles and New York City. But in October of 1971, a film was released to the American public that would serve as a foreshock, heralding the coming cultural realignment that would place the ubiquitous Texas Lone Star squarely on the map, and marking the state as a destination location for film and television production to stand right alongside those aforementioned iconic coastal communities. That film was Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show.

Still from The Last Picture Show (1971) / © Columbia Pictures

Written by Texas native Larry McMurtry and shot on-location in Archer City (a half-hour drive south of our current Governor’s hometown of Wichita Falls), The Last Picture Show is a portrait of a small town at the end of an age, bracing itself for the unknown realities of what is to come. It is only fitting that such a film would mark the beginning of a transition in Texas from one period to the next, from a state content with its position as a backdrop for cowboy pictures and ranch dramas to one actively seeking out and attempting to draw the attention of the major studios and the artists working therein.

On May 24, 1971, the Texas Film Commission was officially created during the 62nd Legislative Session by executive order of Governor Preston Smith. Its mission: to encourage the development of the film-communication industry for the social, economic and educational interest of Texas. The Texas Film Commission was one of the very first of its kind. At the time only two other states operated similar offices. But the governor — an owner of a chain of six movie theaters — was one of the first to recognize the potential for Texas as a destination for Hollywood productions. Like the “New Hollywood” filmmakers working furiously to the east and west (a handful of whom would inevitably find their way to Texas before long), Governor Smith was himself a pioneer, forging ahead into unfamiliar territory and raising the profile of Texas in cinema. At his side was Warren Skaaren, a talented screenwriter who would go on to write films like Beetlejuice (1988) and Batman (1989), who served as the very first executive director of the Texas Film Commission.

Under Skaaren’s leadership, the Texas Film Commission would see a marked increase in film production within the state almost immediately, and his first big get would prove to be a rather influential one: The Getaway (1972). Directed by Sam Peckinpah, an undeniable visionary in his own right, the film starred marquee idols Steve McQueen and Ali McGraw as husband-and-wife bank robbers on the run, making their way from San Antonio to El Paso before finally crossing the border into Mexico. The film was shot on location in 1972 in both San Antonio and El Paso, as well as San Marcos and Huntsville (introducing the Huntsville Unit to movie-going audiences — the prison would eventually serve as a location for James Bridges’ Urban Cowboy only a few years later). The Getaway was the eighth highest-grossing film of 1973, the same year another filmmaker on his way to becoming a well-known cinematic pioneer would also find his way to Texas: Steven Spielberg.

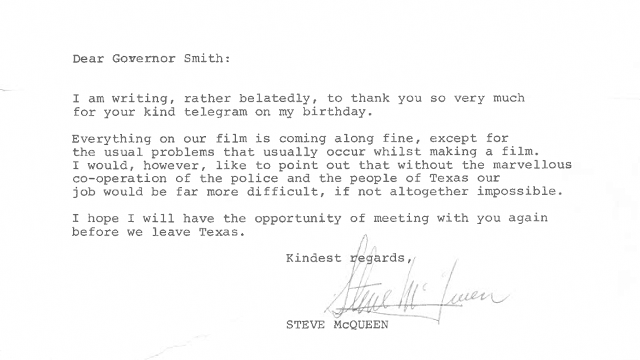

A letter from Steve McQueen to Governor Preston Smith following

production of The Getaway in 1972. View the full letter.

Like The Getaway, Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express used a genuine Texas prison as a filming location to set its stage: Jester State Prison in — where else — Sugarland, Texas. For practical reasons, Floresville doubled for the city of Sugarland on-screen; in addition, the production would capture Pleasanton, Richmond, Converse, Del Rio and San Antonio before all was said and done, all of which also ended up on the screen. The Sugarland Express starred Academy Award-winner Goldie Hawn, but it did not kick-start Spielberg’s career in the way he hoped it might. That would come the following year in 1974 with the release of Jaws, a film that would scare audiences and redefine modern American filmmaking forever by becoming the first blockbuster. But before Jaws was enshrined in the halls of Hollywood history, a handful of Texas artists found themselves working on their own thriller, a low-budget, independent project that would in many ways prove seismically influential in its own right.

In the early 70s, before The Getaway or The Sugarland Express ever rolled across the state lines, two young University of Texas students began work on a screenplay that dealt with, in their own words, “isolation, the woods and darkness.” Written by Kim Henkel and Austin-native Tobe Hooper under the working title Headcheese, the film would come to be known by a name now synonymous with the horror genre: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

The original Texas Chain Saw Massacre house is now

Hooper's in Kingsland. Visit the location.

Filmed over the course of one summer in 1973, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre would redefine the horror film in American cinema. This was both the result of Hooper’s fearless directing as well as the remoteness of the setting, or rather what only appears to be remote. A large part of the fear conjured up by the filmmakers has less to do with the film’s antagonist and more to do with the seclusion of the iconic farmhouse where the protagonists find themselves. As events rapidly proceed from bad to worse, the viewer cannot help but remember how they got there in the first place: driving away from the city and into the countryside, where the only business of note is a gas station (without any gas). In reality, the farmhouse was originally located in Round Rock, no more than a twenty-minute drive from the State Capitol, though to watch the film you’d never guess it. The house would later be relocated to Kingsland, Texas, where it continues to draw visitors to this day. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre would go on to gross roughly 103 times its budget at the box office, and its impact can still be felt in every corner of Hollywood filmmaking to this day. It also served as a declaration to the film world that something was developing down in Texas, something altogether new and directly linked to the region from which it emerged.

Another Texas project from the same period would function as a similar declaration and have a comparable impact on the culture and world around it: Austin City Limits. As far as on-location filmmaking was concerned, the world of the 1970s was far removed from the world we know today. The formation of both state and local film commissions played a sizable role in shifting the focus from coastal to local. In Texas, much of the credit can be attributed to the University of Texas (UT) at Austin, as well as Texans Bill Arhos, Paul Bosner and Bruce Scafe, who provided the catalyst that would kick off a televised music revolution in Texas and show that regular quality production could happen here.

Willie Nelson performs 'Stay All Night, Stay a Little Longer'

on the pilot episode of Austin City Limits, 1974.

In 1974, construction wrapped on a three-building communication complex housing UT’s newly reorganized School of Communication and what would eventually evolve into the Moody College of Communication. Just like that, Austin had two large television studios ready to be put to good use. In the fall of that same year, local PBS affiliate KLRU (then KLRN-TV) would air the pilot for what would become Austin City Limits and establish for the first time a dedicated, local crew base with operations anchored in Austin on an episodic television series.

The rest, as they say, is history. No longer would it prove necessary for productions looking to film in Texas to bring crews from New York or Los Angeles; Texas had, through the relatively simple idea of showcasing Austin’s uniquely diverse local music scene, created an alternative production destination. As a result, the Texas creative workforce would only get bigger from here.

These were some of the first people and projects to come through the state in those nascent years just after the Texas Film Commission’s inception, but they were certainly not the only ones. Volumes could be written on the history of Texas film in the years immediately following the establishment of the state film office. One could touch on Rolling Thunder, written by radical New Hollywood director/screenwriter Paul Schrader, or Joe Dante’s Piranha, iconic to longtime residents of San Marcos and Wimberley. We would be remiss in not mentioning Texas native Eagle Pennell’s groundbreaking 1978 film The Whole Shootin’ Match, which would serve as partial inspiration for Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute. Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974), Michael Anderson’s Logan’s Run (1976), the CBS runaway hit Dallas (1978-1991) — the list goes on and on and on. The legacies of these projects still ripple through Texas culture, as well as the broader, international understanding of Texas with locations like Dallas’ Southfork Ranch serving as an iconic destination for international audiences. Some still feel nearly unaffected by the intervening passage of time — The Texas Chain Saw Massacre feels just as vital today as it did in 1973; the cultural impact of Austin City Limits is felt in the eyes and ears of music lovers from around the world, more so now than ever before.

It is important to acknowledge the rumblings that began to emerge from the technology sector during this decade as well. The influence of the companies that would go on to help define the Texas we know today (Texas Instruments, Motorola, Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation and many more) first began to lay the foundation for the landscape that would play a significantly larger role in media production over the decades to come. But it would not take decades to see the influence of the 70s reflected on the big screen. The impact of those pioneering men and women who had worked to create a bonafide film and production industry in Texas did not suddenly halt at the borderline of the encroaching 80s. Their efforts continued and increased in both scale and scope, bolstered by the successes they had worked so tirelessly to achieve.

The summer of 1979 would see production begin on a film that would set the stage for the very ideas the next decade of Texas films would wrestle with — identity, excess and the growing divide between the rural and the rapidly growing suburban middle class. In many ways it would serve as a bridge between the decades, a film straddling the line between what had passed and what was beginning to reveal itself on the horizon. It has already been mentioned once here and would be the subject of considerable discussion throughout the years following its premiere — a little film released in the summer of 1980 called Urban Cowboy.

Continue: Texas Identity in the 1980s

Written and edited by Steven McCaig and Taylor Hertsenberg. Thank you to our guest editor, Tom Copeland, who served as director of the Texas Film Commission from 1990–1991, 1995–2005.